Vincent Harding: The

Man Behind Dr. King’s Historic Vietnam Speech

Veery Huleatt

“The first time I met Martin Luther

King,” civil rights legend Vincent Harding would later recall, “I

was living in an interracial community in Chicago and we decided we

needed to test our convictions in the Deep South. It was 1958.

“There were six of us, including two

other blacks and three whites, and it was dangerous to travel

together in the same car. In Atlanta, we stopped at the King

residence where he was recovering from the serious stab wound he had

received in New York City. He was in his bedroom in his pajamas, but

Coretta opened the door and welcomed us right into the bedroom. He

congratulated us on having made it safely that far on our trip and

asked us a lot of questions. He was interested in what we were

thinking and why we were doing what we were doing.

“When Martin heard that I was part of

the Mennonite church he said, ‘You are already nonviolent; you

should join us.’ Three years later, in 1961, we did exactly that. I

had just married Rosemarie and the two of us moved to Atlanta where

we and the Kings became neighbors, friends, and co-workers.” The

encounter marked the beginning of a fruitful relationship at the

center of the Civil Rights movement.

Vincent Harding, who died last week

at age 82, never stopped working for his vision of social justice

and community, based on Jesus’ teachings.

Born in Harlem in 1931, Harding

completed college and served in the army, then moved to Chicago to

pursue his doctorate in history. In the course of his studies,

Harding discovered and was inspired by the nonviolent stance of the

sixteenth-century Anabaptists, eventually leading him to join the

interracial Mennonite congregation in Chicago where he would meet

his wife Rosemarie. The witness of the Anabaptists, with their

commitment to peacemaking, nonresistance, mutual care, and communal

life, informed his protests of segregation in America. He

remembered:

We were committed to the law of love

and to the way of community, and we felt very strongly that if we

could not live out that way in the midst of the other way then there

was no such thing as Good News. For us the Good News to a segregated

society was the fact that there were men and women who believed in

another way and who were willing to live that way.

When, on Dr. King’s invitation,

Vincent and Rosemarie moved to Atlanta, they started Mennonite

House, an interracial volunteer center.

To both Harding and King, nonviolence

was not merely a tool for activism, but a way of life. Accordingly,

when the Vietnam War began they both privately opposed it but

hesitated to do so publicly. Harding explained:

From the outset Martin was very clear

that the terror of war always falls on the weakest and poorest

members of the community. He felt that Jesus was serious when he

demanded, “You’ve got to find some other way to respond to evil.”

Martin believed this from the beginning of the war; there is no

question where he stood. But did he dare to come out publicly

against a war? Lyndon Johnson was a key ally in pushing for the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and he

took the war in Vietnam as his personal war. This dilemma created a

struggle within Martin.

You won’t understand this struggle

without first understanding the context. At this point, public

figures did not speak out about the war. There was a kind of

unspoken agreement that this silence is what we all want to do.

Martin knew that many key supporters of the movement would be

unhappy with a public position. So the question for him was when and

how this public position should be taken. He was distressed in his

heart about the position of his own staff. And then came a letter

from the SCLC Board stating that it was the decision of the Board

that King not take this stand.

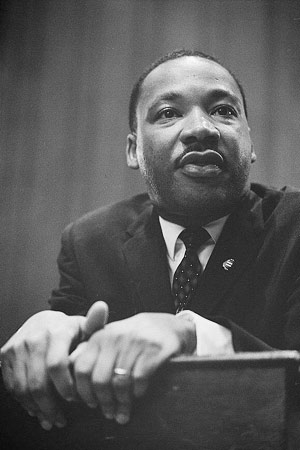

pic

In 1966, however, King concluded that

he could no longer maintain this self-imposed omerta. He turned to

Harding to help him craft the speech – given in April 1967 at

Riverside Church – that would help change the course of history:

Martin knew that he would be speaking

at the deepest level of integrity if the basis on which he spoke was

a religious, a profoundly religious, position. Not a political

position, but one grounded in his religious beliefs. So when he was

invited to Riverside Church to address Clergy and Laity Concerned

about Vietnam, he felt the moment had come.

At the time Martin was traveling

around the country raising money and raising general awareness about

the movement. He did not have time to devote the necessary time and

energy on the speech. So he turned to me to do it (I was a professor

at Spelman College in Atlanta). This thought was rooted in the fact

that he and I had talked many times about this. He trusted me. He

knew that whatever I wrote would be our mutual position. For my

part, I was happy to play this role. Rosemarie and the children had

planned to spend some days of the Christmas holiday with relatives

and so it was in my basement study in that winter of 1966 that I

sought the words that would be said in a way that was King. I was

trying to grasp the words that belonged to both of us.

You have to understand the context

and background of this speech. Black youth was exploding. King could

have chosen to rest on the victories of Selma and Montgomery, the

passage of the Civil Rights Act and the progress on voter rights –

the high moments of his work. But he chose to go to Watts in the

summer of 1965 because he loved those young people in trouble. He

had no plan, no blueprint. The place was still burning and he asked,

“What happened?” A young man told him, “We won.” Martin looked

around him at the destroyed community. “How can you say that?” He

was told, “At least we got everyone to pay attention to us.” This

answer stunned Martin and he began to pay more attention to the

young men and what they were going through. He began to realize that

opposition to the war would not take him away from them, but that in

making his opposition known he was taking a stand on their side.

Entitled “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to

Break Silence,” the speech was a searing indictment of the war and

of its disastrous impact on the struggle for justice at home. It was

probably the most controversial of Martin’s speeches – the New York

Times, the Washington Post, and the NAACP all labeled it a mistake.

Yet at the heart of the words that King crafted with Vincent

Harding’s help is an appeal to the heart of the gospel, evoking

Jesus’ mission to bring “good news to the poor.” King challenged the

nation:

We must move past indecision to

action. We must find new ways to speak for peace in Vietnam and

justice throughout the developing world, a world that borders on our

doors. If we do not act we shall surely be dragged down the long,

dark and shameful corridors of time reserved for those who possess

power without compassion, might without morality, and strength

without sight.

King would fall to an assassin’s

bullet exactly one year to the day after giving this speech.

After King’s death, Harding continued

as a college professor, organized programs for young people, and

wrote several books that document and celebrate the civil rights

movement of the 1960s. In interviews and lectures, he did not focus

on his own past or achievements, but on the movement he took part

in. He pointed students and co-workers to the present and the

future. In his efforts to celebrate the civil rights movement and

Dr. King’s work, Harding resisted what he felt was a tendency to

render them harmless by treating them as past history. In his words:

We pay so little attention to the

real concerns King addressed in his lifetime: poverty, injustice,

the need for community. We like to treat him as a piece of history.

We like to quote him. We like to hold him off at arm’s length as a

great civil rights leader or orator. It’s wonderful that there’s a

holiday named after him, but it’s sad that we can’t make room in our

hearts for his message.

Though a historian by training,

Harding always reminded us to focus on what we can do in the present

rather than dwell on the past. On visits to the Bruderhof, the

community behind Plough, he would focus on inspiring a new

generation to committ to the vision he shared with King. On one such

visit, he addressed a group of young people with these words:

Many people like to idolize the

Martin King of the march on Washington in 1963, but that Martin King

probably would not have been assassinated . . . By 1967, when he

made the speech at Riverside Church, he was speaking about the deep,

fundamental economic injustice which would destroy this country

unless something was done. He was talking about the tremendous

commitment of this country to violence as a way of life, and again,

how that would destroy the country if we did not find another way.

He was talking about the kind of poisoned anti-communism that made

it impossible for the country to understand the longings and the

yearnings of the poor people all over the world.

It is that kind of thing that I speak

about when I speak about the courage of Martin Luther King Jr.,

trying to find a way to live out the love that he really believed

in.

Now that Vincent Harding is gone,

it’s up to us to do just that.

Posted Thursday, May 29, 2014

*** *** ***